Naomi Liz—Moral Compass

When I first visited Cuba in 2004, I was charmed by its culture, experiencing the allure of nostalgia as I entered a space seemingly void of crushing commercialism. At the same time, I sensed a tension between my romanticized version of the Cuba experience and the daily struggles that Cubans face.

Even before I arrived with my study abroad program, I began to realize that Cuba’s modern history was much more than what I’d heard of the United States attempting to “rescue” the Cuban people from an oppressive communist dictator. Since U.S. citizens had been prohibited from traveling to the island for decades, for many Americans that storyline remained one-dimensional, and I left the island with more questions than I’d had when I arrived. “It’s complicated,” I’d say, when other Americans asked me what Cuba was like.

When former President Barack Obama began implementing the policy changes in 2015 and 2016 that made it easier for U.S. citizens to visit the island, traveling to Cuba quickly became a trend, topping lists of “best places to travel” from the likes of Conde Nast Traveler, Travel + Leisure, and The New York Times. While travelers from Europe, Canada, and elsewhere have long known Cuba as a beautiful Caribbean destination, once travelers from the U.S. caught on, international tourism to Cuba climbed almost 18 percent in 2015 and 13 percent in 2016, according to the U.N. World Tourism Organization and the Cuban Ministry of Tourism, respectively.

These days tourism in Cuba is outpacing the rest of the Caribbean. Camelia Gendreau, senior director of corporate communications at Sojern, a company that collects data from travel brands, told Make Change that Cuba ranked fourth in flight and hotel bookings from U.S. travelers among destinations in Latin America and the Caribbean in the first quarter of 2017. In the first quarter of 2016, it ranked 21st.

As interest in traveling to Cuba grows, apprehension about the impact of that tourism is keeping stride. “Everyone is saying to go before it changes,” said Curve Magazine’s Merryn Johns during a recent New York Times Travel Show panel discussion. “But if we go, it’s going to change.”

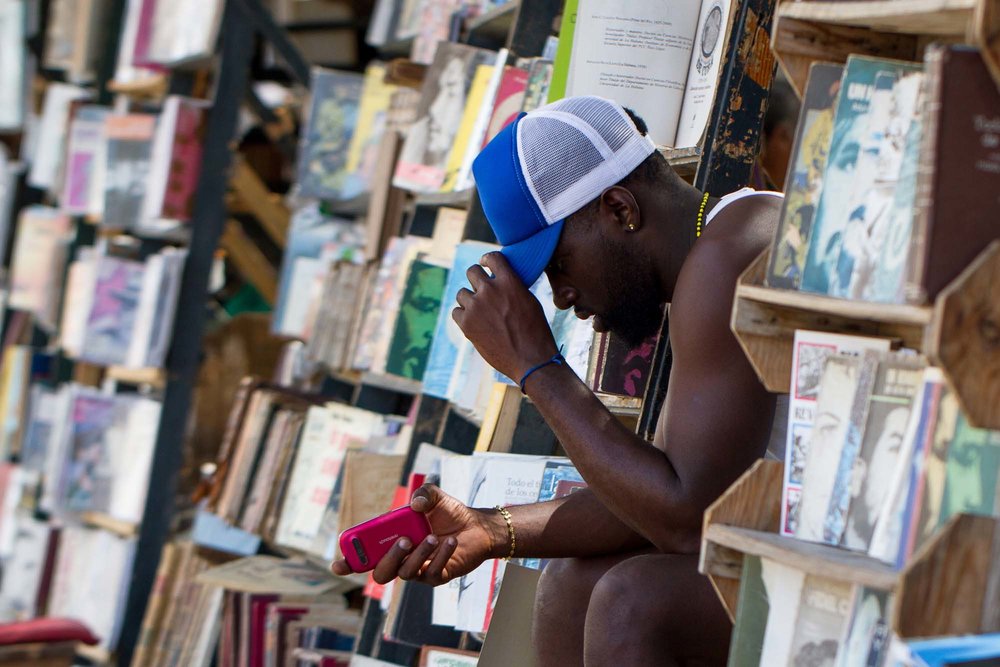

The irony of racing to be a tourist to a country before tourism ruins it would be humorous if it didn’t pose serious consequences to everyday Cubans. While tourists bring money to the local economy, they also have the potential to increase the disparity between those who have access to foreigners’ cash and those who don’t. Cubans are well-acquainted with the side hustle economy, referring to it as la lucha, which means “the fight” or “the struggle.” On my second trip to Cuba in 2014, our tour guide was also an attorney—guiding visitors was something he did on his days off. He told me he took on the extra work so that his daughters wouldn’t have to know the same financial struggle he did. His situation is not unique: In Cuba it is common to find doctors who are also taxi drivers, teachers who rent out rooms to tourists, and other professionals who find a way to carve out a slice of the tourism pie.

In the book Cuba: What Everyone Needs to Know, author Julia E. Sweig shares what happened in the 1990s when the sunny Caribbean island embraced tourism as a way to build their economy: “The industry soon became Cuba’s top earner of foreign exchange. … But it also catalyzed a surge in prostitution and all manner of hustling (of black market cigars, rum, and other products) from Cubans—often with professional degrees—who found it easier, if also degrading, to make a real living with these activities.”

There are some proactive ways to enjoy Cuba’s beauty and culture without leaving a massive, U.S.-shaped footprint on the country.

David Mozer, director of the International Bicycle Fund, suggests that one practical way to have a positive economic impact is to visit communities that don’t normally receive the benefits of international tourism. His organization leads bike tours around the island, and the itineraries are designed to visit towns that are off the beaten path.

Similarly, we should check that pull of nostalgia when we encounter areas seemingly untouched by the 21st century. During the New York Times ethical travel panel, journalist Michael Luongo talked about “ruin porn”—taking Instagram-worthy selfies in front of crumbling buildings. He said that while the decaying classic architecture might be romantic to us as visitors, it’s important to remember that often these structures serve as homes and workspaces for the local population. He encourages visitors to understand the social issues behind such rundown buildings. Why are they deteriorating? How does housing in Cuba compare with other developing nations? Which buildings have been restored, and why those ones?

It’s also vital to understand Cuba’s revolutions and tumultuous history with the United States—which extend beyond the life and actions of Fidel Castro. This history seeps into everything from the value placed on the arts to the ingenuity and resourcefulness demonstrated in Cubans’ everyday lives. If you’re not inclined to research before you go, you can easily learn more by engaging with locals. I’ve been told by more than one Cuban that they aren’t afraid to express their opinions—on the street corners, in the line for the bodega, around a dominoes table—and that “where you have four Cubans, you’ll find five perspectives.”

Another thing to consider is the environmental impact of your stay. The trade embargo had the unintended consequence of helping to preserve the island’s beauty and ecosystem. For instance, a lack of access to pesticides led to the development of organic farming practices. Due to this and limited beach development, Cuba’s coral reefs are some of the healthiest in the Caribbean.

Peggy Goldman, founder and president of Friendly Planet Travel, said there are concerns increased tourism could interfere with that environmental purity. “There are many parts of Cuba that are environmentally sensitive,” she said in an email. “With so much tourism coming into the country, there is fear that many of the protected areas will become spoiled.”

Part of the solution will depend on the regulations that the Cuban government places on new tourism development. But as travelers, we can embrace best practices for sustainability to ensure that our presence doesn’t harm Cuba’s environment: being mindful of waste and water usage, biking or walking whenever possible, and staying in locally-owned accommodations instead of newly built luxury resorts or chain hotels.

Luckily, such accommodations are easy to come by: Cubans were renting out rooms before Airbnb was a household name, and these casas particulares are one of the best ways to experience local hospitality on the island. A combination of hotel shortages, relaxed government regulations on the private sector, and the potential for profiting from an influx of tourists led locals to develop these casas particulares. As Andrew Motiwalla, founder and director of Discover Corps, told me in an email, “The Cuban people are very entrepreneurial. … This has created one of the most dynamic networks of community-based tourism suppliers in the world.”

Traveling to Cuba should come with consideration—of politics, the economy, and the perseverance of culture—but I don’t think these challenges mean that we shouldn’t travel to Cuba. I’m cautiously optimistic about the potential for authentic engagement and the economic impact that increased tourism can have, if we travel mindfully. In addition to doing our part as travelers—learning, forming relationships, sharing experiences—it’s also important to examine our motivations for seeing Cuba before it’s “too late.” We must wrestle with the paradox of being desperate to see a culture before it gets ruined by our very presence.